By Michele Bruni*

Demographic trends are becoming a central issue in East Asia. After the recent debate on China’s recorded population decline, Japan’s demographic trends have now also made the headlines. Japan has allegedly the “world’s most rapidly declining population,” and “in eight years’ time the number of women of childbearing age will fall to a point where population decline cannot be reversed.” Moreover, according to Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, the falling birth rate has placed the country “on the brink of being unable to maintain social functions.” Confronted with this desperate situation, Tokyo is expected to soon “unveil radical countermeasures to try to boost the birth rate, including more financial assistance to help with child rearing, preschool education, nursing care services, and workplace reforms.” A more drastic proposal was offered by a Japanese Yale professor who suggested that the country’s elderly commit mass suicide to lessen their burden on the young.

These catastrophic considerations raise two questions: the first on the exceptionality of the Japan’s demography, the second regarding the appropriateness of the policies suggested.

Firstly, the Japanese demographic situation is, in fact, nothing extraordinary (like China’s, which I already previously remarked on). Its dynamics are similar not only to those of other Asian economies, but to those of many Western ones, including most EU member states, as well.

This statement rests on the consideration that all the planet’s countries are going through a process known as the demographic transition (DT), which brings countries from a situation of high rates of fertility and mortality to a situation of low rates of fertility and mortality, from a situation of population explosion to a situation of population decline. To fully understand the impact of the DT on a country’s socioeconomic situation one must also recall that the DT generates a specific transition in each age group, first in the young, then in the working age population (WAP), and finally in the elderly. Furthermore, over the past 250 years, the planet’s nearly 200 countries have begun to walk down the path of the demographic transition at different moments in time. The consequence is that the countries more advanced along the path of the DT have already reached the final phase of the DT, Japan being one of them.

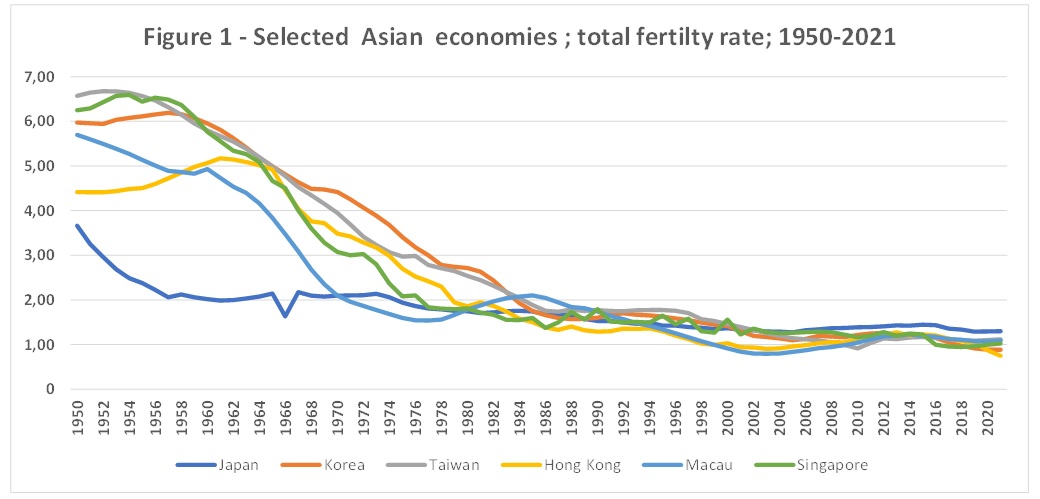

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

When the total fertility rate (TFR) – the average number of children per woman – reaches a value close to 2 (the so-called replacement level) or below it signals that soon the number of children born in a country will not be sufficient to replace the people who die.

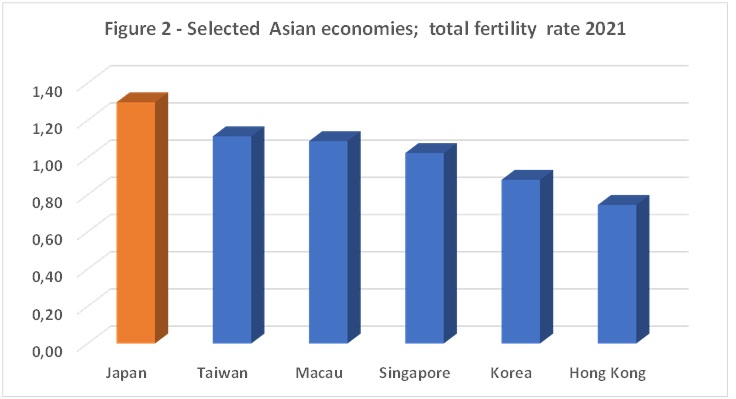

Immediately after WWII, Japan’s TFR was much lower than those of other Asian economies considered in Figure 1. However, it was Macau where the TFR first fell below replacement level (1971), three years before it occurred in Japan (1974). They were then soon joined by Singapore (1977), Hong Kong (1979), Korea (1984) and Taiwan (1985). Presently, Japan’s TFR (1.3) is higher than those of all other Asian economies considered with Hong Kong at 0.75, Korea at 0.88, Singapore at 1.02, Macau at 1.09, and Taiwan at 1.11 (Fig. 2).

Taking a global perspective, Canada’s TFR fell below replacement level in 1973, Europe’s in 1977, and Australia’s in 1978. In 2021, the TFRs of all these countries and regions were still below replacement level, with some European countries registering TFRs close or even inferior to that of Japan, including Italy (1.28) and Spain (1.28). Let’s finally add that, according to the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN/DESA), the planet’s TFR will fall below replacement level in less than 50 years and the world population will start to decline in 2086.

In conclusion, Japan’s situation is nothing exceptional. However, what does make Japan different is Tokyo’s stubborn refusal to recognize that its economy needs foreign labor. While EU member states are also doing everything possible to reject migrants, they have received millions of them over the past decades. Moreover, it is a fact that their economies could not have grown without resorting to exploiting them, a statement that holds true also for the US.

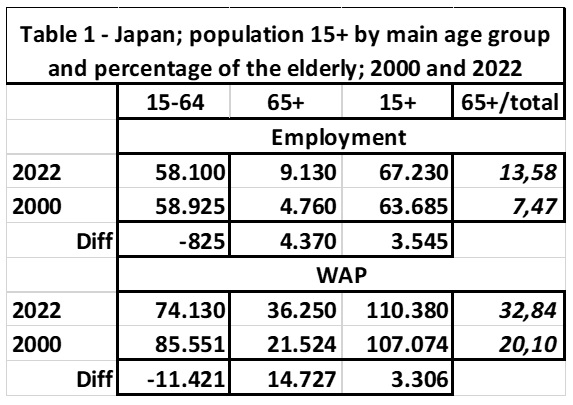

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

To put Japan’s planned pronatalist measures in the right perspective, it is necessary to illustrate Japan demographic problems and verify in what measure an increase in the number of births could solve them. It seems to me that the central demographic problem Japan must face, as all countries that have reached this same phase of the DT, is a shrinking labor supply, which limits the possibility to raise the employment level.

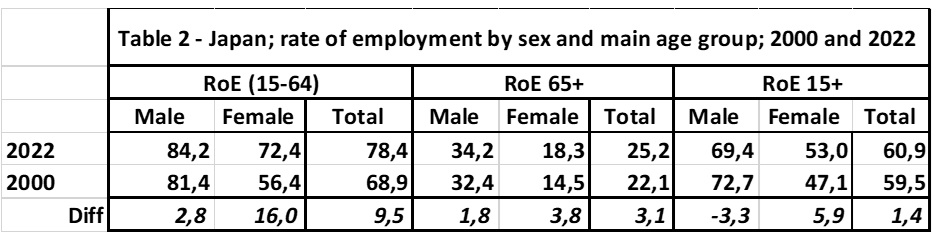

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

From 2000 to 2022, Japan’s population aged 15 and above increased by around 3.3 million (3%), the balance between a dramatic decline of the population in the 15-64 age bracket (-11.4 million, -13.4%) and a massive increase of the elderly (+14.7 million, +68.4%). In the same period, while registering some notable cyclical fluctuations, employment increased by 3.5 million (5.3%) (Table 1).

Japan’s labor market confronted this difficult situation with a set of strategies. Firstly, increasing the rate of employment (RoE) of the population aged 15 to 64 by almost ten percentage points (from 68.8% to 78.4%) (Table 2). Despite this notable feat, the number of jobs held by this age group declined by 825,000. Next, increasing the number of jobs held by the elderly by almost 4.4 million, with their share of the employed population growing from 7.5% to 13.6%. Finally, increasing the involvement of women in the labor market, with the percentage of jobs held by them increasing from 40.8% to 45%. This is also well-reflected in how the female RoE for the 15-64 age group increased from 56.4% to 72.4% and the elderly female RoE grew from 14.5% to 18.3%. Now, the interesting question is whether Japan’s labor market could repeat this strategy from 2022 to 2045.

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

It is sufficient to peruse UN/DESA’s population forecast to realize that the answer is a straightforward no. In the next 23 years, in absence of immigration, Japan’s population aged 15 and above is projected to decrease by 14 million, the result of a balance between a decline of 18 million of the WAP proper and an increase of 4 million of the elderly. Assuming the same rate of employment growth registered between 2000 and 2022 and an unlikely RoE of 80% for the population aged 15 to 64, to satisfy the labor demand would require 2 out of 3 Japanese aged 65 or older to hold a job! This brings us to the following question i.e., will policies aimed to increase fertility allow Japan to do without foreign labor?

The history of measures aimed at increasing fertility (and of their failures) is a long one. Among the first and certainly most comprehensive, but also less successful, we can recall the lex Iulia and the Lex Papia Poppaea, enacted in Ancient Rome under Emperor Augustus. They contained a vast array of incentives and disincentives both for single people and married couples, including an innovative ban on wearing jewelry and using sedan chairs for women over 24 who were still unmarried or married without children (today a similar ban would probably concern metro, buses, cars, and taxis).

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

Source: Own elaboration based on UNDESA (2022)

During the interwar period, pronatalist measures were adopted by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, but also by France. After WWII, numerous states such as Romania and other Eastern European countries joined France in enacting pronatalist measures, albeit of very different nature and level of coerciveness. More recently, persisting low fertility rates have pushed numerous countries, including Australia and Italy, to adopt pronatalist measures. However, with very few and limited exceptions, these measures have failed to produce relevant results.

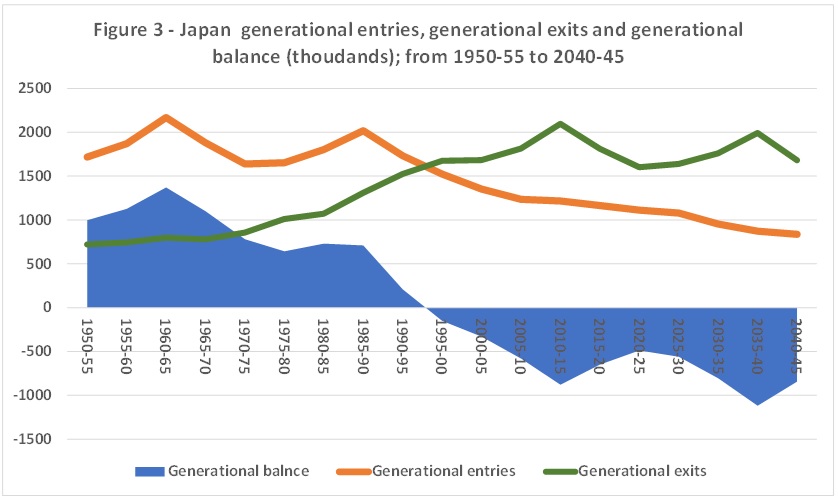

However, the fundamental point is another. An increase in the number of births requires around 20 years to have an impact on the labor supply. As shown by Figure 3, generational entries into the WAP (15-64) have been lower than generational exits since the end of the last century and from now to 2045 the yearly difference will range from 500,000 to 1.1 million. Data shows that just to close this gap between generational entries into and generational exits from the WAP by around the middle of the century, the pronatalist measures that Prime Minister Kishida is planning to propose would have to increase the number of children born yearly to 1.6 million (by then number of generational exits) by 2030, i.e., double the present value. Thus, even the dystopic visions of mass suicide of the elderly would not improve the labor market situation. Moreover, taking everything into account, it is not evident whether the elderly are a burden on or a resource for the country.

Therefore, it seems evident that Japan can avoid future economic downturns only by accepting that its labor market needs massive injections of foreign workers. Additionally, it should also be self-evident that it is much better to manage migration flows coherent in a rational and humane way, by organizing them based on the qualitative and quantitative needs of the market, rather than fighting a losing battle against massive flows of illegal but necessary workers.

* Michele Bruni is a member of the Center for the Analysis of Public Policies (CAPP) of the Faculty of Economics, University of Modena, Italy